A family friend gave birth to a newborn a few days ago. Everyone gathered around the baby and played with the her soft hands, her button nose, and her tiny feet. People cooed and made funny noises to the baby. The people commented on her features.

“She’s as tiny as the aunts – now that’s a trait!” Everyone giggles.

“She got her abuelita’s nose. Who would’ve thought?” Everyone laughs. The abuelita gently smiles. She asks someone to bring her the baby.

“But she is so Indian, too bad. She would’ve looked better if she were as light as her father.” Everyone sighs. Even the grandmother.

Hold up!

Are you hearing what I’m hearing?

“But she is so Indian, too bad.”

I asked a bit annoyed, “What do you mean ‘too bad’?”

“She is tipica, you know. Super brown and chola hair. Plus she was born in the USA.” Then, she turns to the great-aunts with a question. “In our family, we have Spanish blood. Blue eyes. Thin nose. Light skin. But I wonder why this baby is so brown in the first place?”

They sigh again as if this precious gift of life FAILED to inherit the most “beautiful” physical trait: the White features.

My mother darted the DON’T-YOU-START look. It was not the right time and place to discuss such matters. But I thought about the times my very own family used to say things like this to us – to the new generation.

Both of my grandmothers acted like they were on top of the world when they lived in New York City – the American dream. Their Ecuadorian families respected them for their courage to face a new life and a new culture. Therefore, both families assumed my grandmothers had tons of money with their new acquired social status as las americana.

My paternal grandmother wore her hair pineapple style. It was even the pineapple color: blonde. She was a tall and robust woman. She wore Macy’s high quality dresses, a gold watch, and pearl necklaces – even when she was at home all day. She made sure she walked like a Hollywood star in her neighborhood – and people respected her.

So one day, I asked her out of curiosity, “Mamí, who are our ancestors?” She took care of 8 kids at the time, including me, so my question came out as absurd.

“We’re Ecuadorians, my love. We come from the Spanish Barrera family. It is said that a long time ago, when Ecuador was still a colony, the Spanish Barrera started a new life there – like us in New York City. The father figure owned a hacienda. He had three daughters, one of which was your Great-great-great Grandma Eva. Well, she was a writer, a poet, and a novelist. Her writing got published in many newspapers in Ecuador. But that’s a whole other story. Eva fell in love with the overseer of her hacienda. He was poor like the rest of them, and her father didn’t like that because they met in secret.”

“The father gave Eva an ultimatum – either she goes with her lover or she stays with the family. She chose to leave with the overseer, rode their horse, and started a new life elsewhere. She married the man, but she lost her inheritance – something we could all make use of nowadays.”

One of my cousins shattered the plates in the kitchen. She left me with more questions.

Later that day, I found her sitting next to the window. She stared at the kids playing basketball in the streets and young mothers talking to their husbands in the park. She could see the birds fly over the trees. She felt the sun shine her face.

“Abuelita, so what happened to them?” I asked with a chipmunk’s voice in the background.

“Who?” She was caught off guard. “What are you talking about?”

“Eva and her husband,” I said shrugging.

“Yes, yes, Santísimo,” she said recollecting her thoughts. She positioned herself to face me even though the sun shone her cheek. Her pineapple hair looked white with the reflection.

“Eva and her lover left the hacienda and rode through the forest, the hills, the rivers, and the mountains. Many day later, they finally arrived to Guayaquil. This is where they started their new family. This is where their kids grew up to be healthy and strong. This is where they had their grandchildren.”

“Then came a day when Eva got sick and was sent to a private clinic. A doctor checked her health, prescribed her medicine, and talked to her husband about possible cure. Ay Santísmo, you should’ve seen their reaction when the doctor looked through her records and asked, ‘You’re Eva from the Molestina family?’ She nodded. ‘Tía, I’m your nephew. We’ve been looking for you all these years.’ So the story goes, they talked for weeks until the day she died. She did not get to see her family, but she sure died knowing that at least she was able to reconnect with somebody.”

“Wow,” I tell her. “What about the lover?”

“We don’t know much of his story. What’s important is he married a woman of high class – we have Spanish blood!” She emphasized. Then I look closer at her pineapple hair and like the fruit itself she had hints of black hair.

Years later, I did my independent research in addition to my college work to find out about Eva’s husband. I read books to learn more on Ecuadorian history. I searched online to track the Molestina family. I pulled scholarly articles from JSTOR about haciendas, colonial Ecuador, slaves, etc.. I did not find his name, but I found a story that spoke on behalf of people like him – whose stories were left in the forgotten.

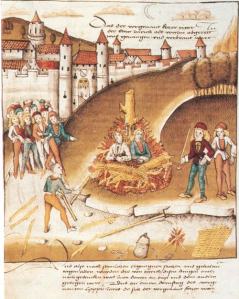

In colonial Ecuador, haciendas expropriated Indigenous people from their land. Indigenous people were forced to work as slaves. They were baptized into their master’s surname, and took his culture, his religion, and his tradition.

There was the Casta, too – a system that categorized people according to racial backgrounds. The Casta included the following: the Peninsulares (the Spanish); the Criollos (Spanish-born in the colonies); the mestizos (mixed-Spanish/Indigenous); mulattos (mixed-Spanish/African); Indios (Indigenous); and Black (Africans), and a set of ridiculous hybrids based on blood quantum (sambo, cholo, castizo, etc.). The system encouraged the separation of thought process, behavior, expectation, and stereotype associated with each racial category – which, in turn, empowered the elite and suppressed the discriminated.

The general logic: The lighter your skin, the better your socio-economic position in a white-mestizo colonial society.

The Casta perpetuated for many generations after the colonial era. Actually, we ARE living the same system where identifying as a Mestizo is much more convenient than identifying as an Indigenous or as Mulatto. The worst part is the Casta is in everyone’s mind in Latin America. The future of your kids depend on who you marry, who you socialize with, and who you work for. If you look “Indio” or” cholo,” society will encourage you – through media, politics, and costumbres – to marry a white-person to strengthen your socio-economic position in the future. For those who prefer not to mix, Indigenous people have the option to abandon their traditional clothing, their braids, and their language, and in their place, wear Western clothing, comb their hair, and speak Spanish fluently. Therefore, they can pass as mestizos.

This is the narrative of mixed-Indigenous and Indigenous people when it comes to culture, politics, and land sovereignty in relations to blood quantum and ethnic labels. The Casta empowers the elite and the lighter-mestizo and castigates the brown-mestizo, Indigenous people, mulattos, and Afro-Ecuadorians.

“But she is so Indian, too bad.”

The Casta also perpetuates stereotypes associated with Indianess. For example, why do we have shows like La India Maria or La Paisana Jacinta that portray Indigenous women as “stupid” and “brutes” – often ridiculed by urban mestizos? When I was little, my entire family watched La India Maria and laughed at her “Indianness” in urban spaces where she was always corrected by the society. Why do we say un “indio civilizado” versus un “indio salvaje”? What does that even mean? Sometimes, I think there is no difference between the both. It just empowers the civilized – the one who assimilated, the one who adapted, and the one who was colonized – to disenfranchise the savage – the one who wore plumes, the one who worshiped rocks, and the one who walked naked in the forest.

“Don’t be Indian.”

This is a common phrase used in Latin America to correct a person who does something “stupid.” Once again, this phrase incorrectly protrays Indigenous people as uneducated – unless they assimilate.

“Eres Cholo” or “Vos es Longo”

In Ecuador, a lot of people use “cholo” and “longo” to discriminate Indigenous and mixed-Indigenous people. In the Ecuadorian context, “un cholo” is associated with stupidity and backwardness. In Guayaquil, “un cholo” is a person from el campo. “Un cholo” is a person with strong Indigenous features and super moreno skin. “Un cholo” is a wannabe mestizo who tries to fit in dominant urban society.

In Quito, “un longo” is a person from rural Andean towns. “Un longo” is a person with existing Indigenous ties to his or her current place of origin. “Un longo” is a wannabe-white.

Both serve to put down a people who might be proud of their Indigenous roots, but feel the need to cover up their cholo-ness and longo-ness under the mestizo label.”Cholo” and “longo” is equivalent to “indio” and “stupid.” Who wants to identify as such in the social context? In family settings? In the census?

I was recently corrected by a reader that the Ecuadorian government does provide an opportunity for Ecuadorians to identify as “Indigenous” in the census. I want to give a shout out to the person who brought this to my attention. Perhaps I was not clear with what I wanted to say so I will elaborate here. The Ecuadorian government allows the following options: White, Mestizo, Indigenous, Afro-Ecuadorian, and Montubio – the latter is a new addition to the mixed (Blanco, Indigenous, and Afro) population in the Ecuadorian Coast. However, the real challenge is how does the census get to the people? Are they accessible or inaccessible to ethnic groups in various locations? Is the government still excluding other ethnic labels that we do not know of?

In my article, recently published in Indian Country Today Network Media, I mention that Comuneros in Santa Elena Peninsula had the following option to identity as such: Blanco, Mulatto, and Mestizo (please consider the aforementioned correction in the last paragraph which includes all ethnic labels since 2010). What I meant to say was their specific ethnic label was not included in the census. In this article, Comuneros from Chanduy district complain the following:

In Santa Elena, the Comuneros want to identity as Cholos. And they complain that their ethnic label is not included in the census.

Comuneros feel the ethnic label Mestizo does NOT correctly identify their cultural history, tradition, and people. Comuneros are in the process of re-claiming their Wankavilka roots to protect their lands and cultures from expropriation. In their opinion, “Cholo” becomes a tool that empowers them and separates them from the Indigenous and Mestizo space for various of reasons. In my oral tradition, my family says we come Indigenous ancestors, but we identify as Comuneros today.

In Santa Elena, comuneros identify as Cholos because it closely describes their existence as an ethnic group that acculturates from one era to the other -pulling a rich history of 12,000 year-old-Indigenous culture and including new cultural elements to their Comunero identity. “Indigenous” to them means a group of people who maintain their traditional clothing, roots, language, and land since the beginning of time.

Cholos live in their ancestral land and maintain their Indigenous culture, but they adapt to new clothing and language in order to keep up with global technology and better use of communal economy. I’m a Comunero from my mother’s side. I speak English fluently and acculturate American elements as part of my identity. But I also pull Spanish, Kichwa, Huancavilca, and Sumpa cultures with me – and this does not make me any less Indigenous.

The ethnic label “Cholo” is not in the Ecuadorian census – which means they have two options: Mestizos or Indigenous. They oblige-voluntary identify as Mestizo – a blanket term that covers up discrimination and encourages assimilation of all ethnic groups regardless of their historical origins, colonial trauma, and ethnic traditions. They do not feel comfortable identifying as Indigenous because some, more than others, believe they are not Indigenous as the Tsa’chilas, Kayambi, or Shuar Nations, to name just a few. Also, they get backlash from Indigenous communities because Comuneros do not “look” Indigenous, and by this, they mean Comuneros do not wear traditional clothing or speak their Native tongue. In Silvia Alvarez’s research, however, Comuneros are the most “Indio” in the Ecuadorian coast and Andes regions. In fact, they are full blood Indigenous people who possess a half a million hectares which makes them the largest ethnic group in Ecuador.

The mestizo concept does not equally glorify two cultures. The dominant Euro-centric culture overpowers the Indigenous one – providing an opportunity for discrimination with words like “cholo” and “longo,” land expropriation, and much more. In this case, ethnic Comuneros with “mestizo” label become an invisible ethnic group in the Ecuadorian coast – a total of 200,000 plus people – at risk of losing their lands. Large corporations expropriate them from their ancestral land due to the mislabeling since 1982.

Comuneros demonstrate that language is key to empower a people. Cholo is a negative term in Latin America, but Comuneros transformed it into a positive label for self-identification.

This goes to all of us – not just Indigenous people in the Americas. Have you ever wonder how one word can impact another person’s self-esteem? Have you asked yourself what the word originally means? Let’s take a look at how we can raise awareness in our communities.

I hear kids in school say “that’s gay” when they really mean to say “that sucks” or “too bad.” Using the word “gay” hurt a large group of people who identify as queer, gay, bisexual, lesbian, and transgender, and serves to reinforce negative connotations and stereotypes with the word. The original meaning is “joyful” and “happy.” The word “gay” can negatively impact a person’s self-esteem when used incorrectly.

In Ecuador, the Tsa’chilas People had a reputation based on the “one word” every Ecuadorian used: Los Colorados. They were called “colorados” because of the red taint on their hair, but the Tsa’chilas collectively felt it was offensive to their people, their history, and their youth. The red means salvation to them. It saved them from an epidemic disease that hit their region centuries ago. They wear it in honor of the sacred medicine. Even though it’s part of their identity, they feel it does not correctly identify them. The Tsa’chilas pushed for national recognition of their true name. Now, they are referred to as Tsa’chilas, not Colorados – thanks to raising awareness.

Even using simple phrases like “the lighter, the better” can be damaging to those who do not have light skin color. They feel ugly and out of place . Instead of celebrating diversity, only one color rules them all. Like in the movie Precious, she sees herself as WHITE in the mirror – a reality that many people of color sometimes try to live up to.

The next time I see a baby that is too brown or too cholo-looking, I will raise awareness by asking people “Why would you use x word to describe x situation?” Think about it – just by asking you can change the world one step at a time.